MY ROLES

UX Research

Game Design

Learning Design

DURATION

Nov 2018 - Jul 2019

(9 months)

Challenge: The gap in the current art education

A common challenge in the development of creativity is that students perceive creativity as an innate personality and ability and do not believe in their own creative potential (Boden, 2004; Kelley & Kelley, 2013; Davies, 2000). Creativity is in demand in many fields, including art, business, and technology (Davies, 2000; Kelley & Kelley, 2013), yet our current education system provides insufficient support to the development of children’s creativity, due to limited teaching resources and a limited budget (Brooks, 2001; Spohn, 2008). Moreover, existing educational products do not consistently incorporate learning mechanics to discover children’s creative potential. Lastly, curriculums in school often move forward too fast without leaving children enough time to explore creativity (White, 2018) and cultivate an experimental attitude.

Seen together, these conditions limit students’ development in artistic creativity throughout their academic career.

Figure 1. Issues in the current education system

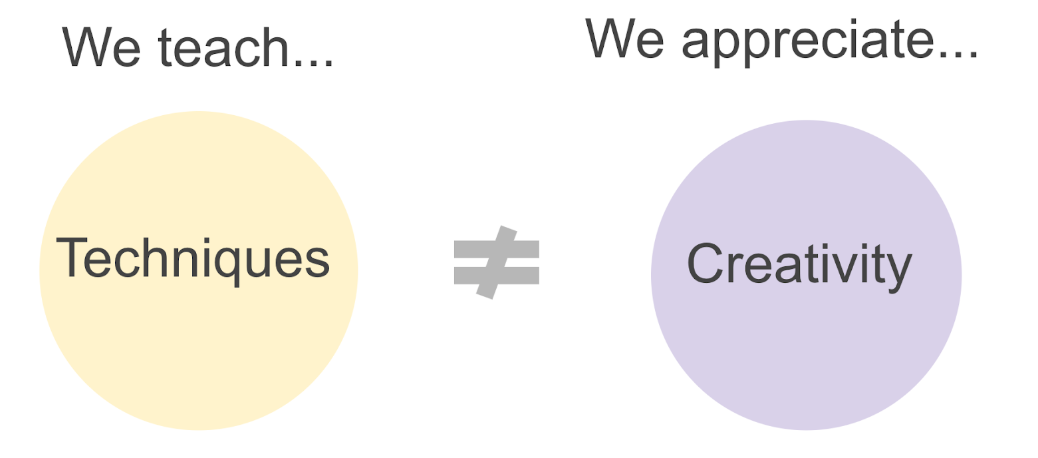

Figure 2. Challenge

There is a gap between what we teach and what we appreciate (see Figure 1). We celebrate great artists’ creativity, but often teach children rote techniques rather than encouraging them to be creative.

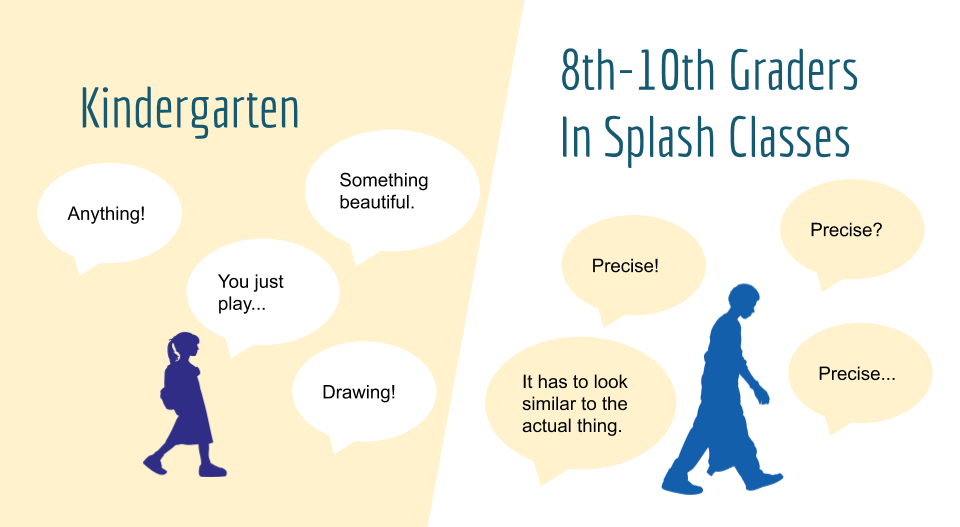

In order to investigate how students in different age groups perceived art, I asked kindergarten and middle school students to define art. While kindergarten students gave a diverse range of answers, middle school students emphasized more on the ability of drawing precisely (see Figure 2). According to my interviews with art educators and local artists, though artists’ creativity often built upon sufficient techniques, artists’ creative confidence was the cornerstone in their process of creation. Studies show that support and feedback from teachers in traditional environments can help students build creative confidence (Davies, 2000), which may help students move beyond the concern of being imprecise, and eventually cultivate an experimental attitude (Hillis, 2018). Students identified the need for close, individual support and endorsement from teachers; when such support was absent, they felt negative about their creative achievement (Davies, 2000). It is possible to build these skills in schools, but it is time-intensive and requires support from teachers.

Figure 3. In response to an open-ended question “what is art?” : a comparison between kindergarten students and middle school students' answers.

Research indicates that art education not only promotes children’s creativity, but also improves students’ overall school performance and involvement in community service and pro-social activities (Catterall, 2009). Students who experience learning difficulty in school and come from low-income families benefit from art learning even more than privileged students (Catterall, 2009; White, 2018). The positive impact of art education lasts through adulthood. However, art classes and resources tend to be the first cut in schools with insufficient budget (White, 2018), especially in underserved communities. Thus, art education and its benefits are unequally distributed, perpetuating the opportunity gap. To address the challenges that we are facing in creative art education, I believe we can design a scalable, low-cost web learning tool that encourages students to explore visual art in a playful, safe space.

Iterations and Play-tests

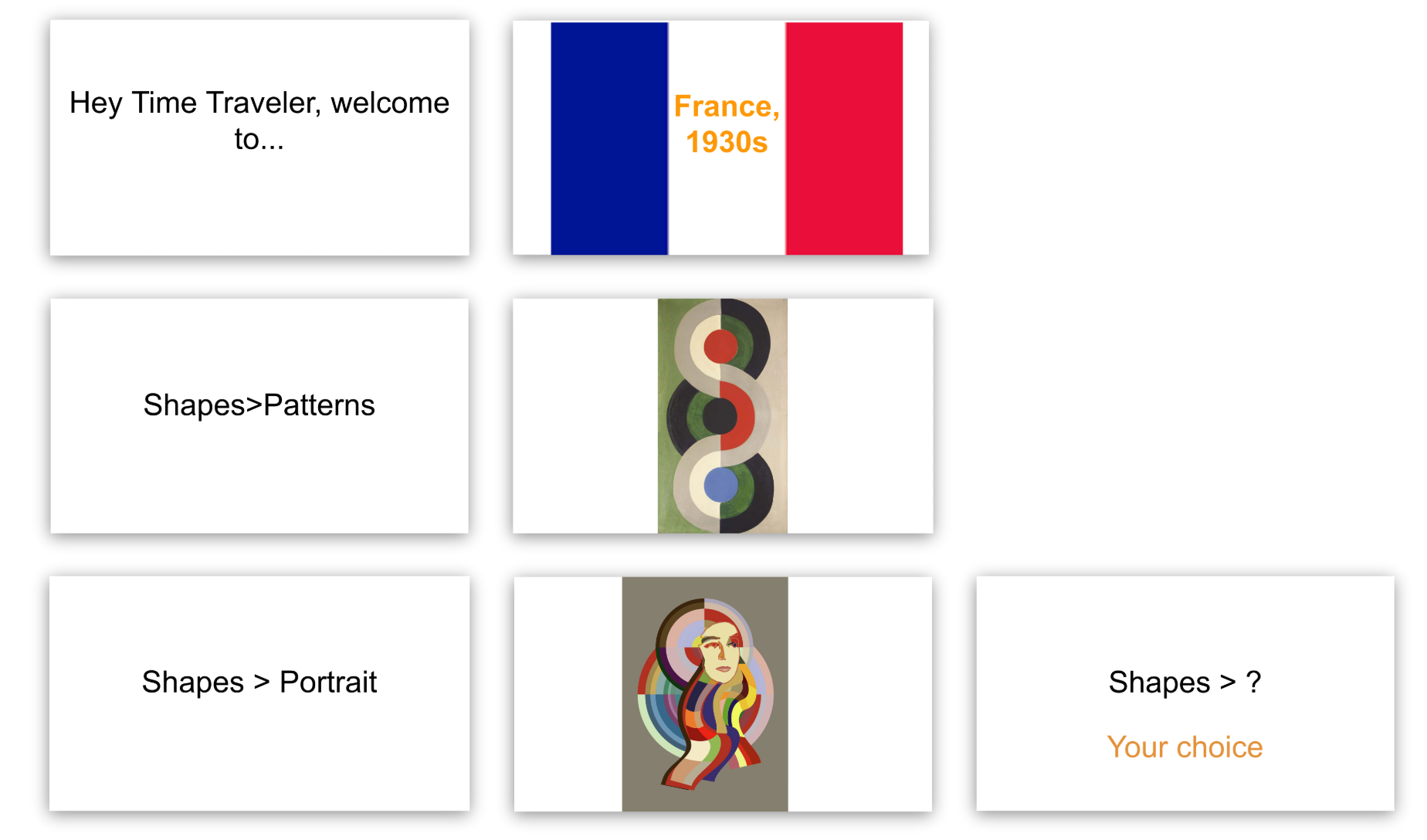

This version of conceptual prototype was developed based on the time travel idea. Lately I have been thinking more about what artists and content to include in the game. As the game targets late elementary and middle school students, I tried to find artists whose works reflect the principles of visual elements and color theory. The French Artist Sonia Delaunay's colorful, geometric paintings can be a great starting point for someone with minimal experience in art.

Instruction and supplemental materials, including a set of markers, printed geometric shapes, and six decks of sticky notes in different colors were prepared for furture user testings.

The six decks of sticky notes will be arranged in two rows, "time" and "country", as a fake mechanism of "time travel". The participant will be asked to choose one deck from each row, in order to determine the time period and country that the participant will travel to.

The participant will cut out shapes from the rinted geometric shapes to complete the task.

Mid-Fi Prototypes

Instead of letting players draw within a frame, I decided to remove the frame so that users can draw more freely (and more immersively). I also reframed the narrative of the challenge prompt to emphasize on helping the artist, and using creativity to take the challenge.

Rather than giving purely positive feedback like "well done", the virtual artist (aka the game version Warhol) provided a slightly critical feedback and suggested players to try the next level of challenge for improvement.

Players will have the option to challenge a more advanced module in future.

I have not build the next level yet; the idea was to get students experience a little frustration and chaos in the first level, and encourage them to become mindful at creating patterns out of visual elements in the second level.

I kept thinking about changing the concept of traveling on a world map to traveling in different time periods and cities. Because I did not feel strong about the mechanics of viewing multiple artists from different time periods in one city gallery. Children might become confused about the time periods and cultural contexts when they see artists mixing up in the gallery.

Next Steps

Preliminary results from user tests and studies suggest that the game is an engaging, playful experience that encourages learners to experiment with different art techniques, though more scaffolds are needed to help learners transit from emulating to challenging artists’ styles. Along with testing its long-term effect on children’s creative confidence and creativity, I will push the game further on content creation, technical development and partnership with schools.

1)Content Creation

The current game only supports modules of two artists. My next step is to create more modules for female artists and non-western artists. In addition to the game itself, I will also provide guides and resources for parents and educators to support further exploration in art. After the version 1.0 of the game launches online in October 2019, new modules and activities will be updated periodically depending on the production cycle.

2)Technical Development

Currently students can visit the website of Nartshell and start their exploration in the Unity game at any time, but the site is not optimized for cross-platform functionality and data-driven features. The next version of Nartshell will be built in HTML5 instead of Unity, aiming for faster loading speed and integration with a user database. Building in HTML5 also prepares the game to become an open-source project in the future by making it possible for other people to contribute.

2)Partnership

The game will be introduced to students by collaborating with schools, daycare centers, afterschool programs and local public libraries in underserved communities. Currently I am in the process of searching for a school or an afterschool program to partner with. With regard to financial sustainability, there are two potential plans for future development of the game. The final plan will be determined after testing the latest game prototype, and consulting with schools and school districts. First, integrating the game with an existing learning platform like Schoology. Updates of new modules after the version 1.0 can charge organizations (e.g., schools, daycare centers) for memberships at a low cost. Second, making the game a free, open-source project that other game developers and educators can contribute, with the potential of students becoming creators or curators of the game content.

Amabile, T. M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: A consensual assessment technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(5), 997-1013. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.5.997.

Barata, G., Gama, S., Fonseca, M. J., & Gonçalves, D. (2013). Improving student creativity with gamification and virtual worlds. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Gameful Design, Research, and Applications(pp. 95-98). ACM.

Boden, M. A. (2004). The creative mind: Myths and mechanisms. Routledge.

Brooks, A. C. (2001). Who opposes government arts funding?. Public Choice, 108(3-4), 355-367.

Catterall, James S. (2009). Doing well and doing good by doing art: The effects of education in the visual and performing arts on the achievements and values of young adults. Los Angeles/London: Imagination Group/I-Group Books.

Chen, C., Kasof, J., Himsel, A. J., Greenberger, E., Dong, Q., & Xue, G. (2002). Creativity in drawings of geometric shapes: A cross-cultural examination with the consensual assessment technique. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(2), 171-187.

Cutumisu, M., Blair, K. P., Chin, D. B., & Schwartz, D. L. (2015). Posterlet: A game-based assessment of children's choices to seek feedback and to revise. Journal of Learning Analytics, 2(1), 49-71.

Davies, T. (2000). Confidence! Its role in the creative teaching and learning of design and technology. Volume 12 Issue 1 (fall 2000).

Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., & Pretz, J. (1998). Can the promise of reward increase creativity? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 704-714. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.704

Eisner, E. W. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. Yale University Press.

Erhel, S., & Jamet, E. (2013). Digital game-based learning: Impact of instructions and feedback on motivation and learning effectiveness. Computers & Education, 67, 156-167.

Gardner, H., & Davis, K. (2013). The app generation: How today's youth navigate identity, intimacy, and imagination in a digital world. Yale University Press.

Hillis, N. (2018). The artist's journey: Bold strokes to spark creativity.

Kelley, T., & Kelley, D. (2013). Creative confidence: Unleashing the creative potential within us all. Currency.

Rowsell, J., Morrell, E., & Alvermann, D. E. (2017). Confronting the digital divide: Debunking brave new world discourses. The Reading Teacher, 71(2), 157-165.

Schunk, D. H. (2003). Self-efficacy for reading and writing: Influence of modeling, goal setting, and self-evaluation. Reading &Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 159-172.

Spohn, C. (2008). Teacher perspectives on No Child Left Behind and arts education: A case study. Arts Education Policy Review, 109(4), 3-12.

White, Katie. (2018) Unlocked: Assessment As the Key to Everyday Creativity in the Classroom. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary educational psychology, 25(1), 82-91.